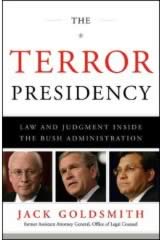

The Terror Presidency: Law and Judgment Inside the Bush Administration

The Terror Presidency: Law and Judgment Inside the Bush Administration

Jack Goldsmith

Norton, 2007

256 pp.

The problem with hiring competent, principled attorneys is they don’t always tell you what you want to hear. That made Jack Goldsmith, briefly the assistant attorney general in charge of the Office of Legal Counsel, an inconvenient Bush administration appointee. His tale of bureaucratic and legal infighting is simultaneously interesting and important.

Goldsmith’s appointment grew out of a disagreement between Attorney General John Ashcroft and White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales. They often clashed: Gonzales usually won, even though he was usually wrong.

Goldsmith’s appointment grew out of a disagreement between Attorney General John Ashcroft and White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales. They often clashed: Gonzales usually won, even though he was usually wrong.

Explains Goldsmith, Gonzales “defeated Ashcroft’s effort to take a hard-line stance against affirmative action before the Supreme Court; he led the creation of military commissions, which Ashcroft never liked; and he put the brakes on Ashcroft’s attempt to implement an aggressive interpretation of gun rights under the Second Amendment.” They also battled over the FISA program, in which the attorney general turned out to be a defender of civil liberties.

The OLC position became another battle.

The White House wanted John Yoo, an OLC deputy, to head the office, which assesses the legality of presidential actions. Yoo authored many of the early opinions on torture and enemy combatants and was a strong advocate of the unitary executive – the view that, to paraphrase French King Louis XIV, the president is the state.

Technically on Ashcroft’s staff, Yoo “took his instructions mainly from Gonzales, and he sometimes gave Gonzales opinions and verbal advice without fully running matters by the attorney general,” writes Goldsmith. So Ashcroft said no to Yoo. Goldsmith, special counsel to the general counsel at the Defense Department, became the compromise choice.

Goldsmith was no shrinking violet when it came to presidential power. But Goldsmith soon discovered the downside of not believing President Bush to be the reincarnation of the famed Sun King. His White House interlocutors failed to ask the right questions. Goldsmith writes:

"We did not, however, talk about things I didn’t know about at the time, such as the National Security Agency’s Terrorist Surveillance Program, or what President Bush would later describe as the CIA’s ‘tough’ interrogation regime. Nor did we talk about my disagreements with administration policy – disagreements that [his Pentagon boss, Jim] Haynes knew about but apparently did not convey to the White House. While I believed the government could detain enemy combatants, I thought it needed more elaborate procedures for identifying and detaining them, and had been working on this issue since I arrived at the Pentagon. I had long argued to Haynes that the administration should embrace rather than resist judicial review of its wartime legal policy decisions. I could not understand why the administration failed to work with a Congress controlled by its own party to put all of its anti-terrorism policies on a sounder legal footing."

President Bill Clinton also made expansive claims of executive power, observes Goldsmith. However, this administration has pushed much further. The terrorist attacks of 9/11 triggered a demand for ever more expansive authority without accountability, and the OLC was expected to provide the necessary legal justification.

While it is widely thought that administration advocates of an all-powerful presidency don’t care about the Constitution, Goldsmith disagrees. Both David Addington “and his boss Cheney seemed to care passionately about the Constitution as they understood it. That is why they fought so hard to return the presidency to what they viewed as its rightful constitutional place.” He rejects the charge that they manipulated 9/11 to advance their preexisting agenda, but acknowledges that “their unusual conception of presidential prerogative influenced everything they did to meet the post-9/11 threat.”

The problem of squaring the circle soon became apparent to Goldsmith. Today the law increasingly frames, regulates, and interferes with combat operations. Thus, legal opinions, like those from OLC, have enormous operational importance. (This issue is both fascinating and disturbing, and deserves a book of its own.)

In this circumstance, writes Goldsmith, “Yoo was a godsend. In close coordination with the War Council, he pumped out opinions on all manner of terrorism-related topics with a clarity of approval that emboldened the hesitant bureaucracy.” Unfortunately for Goldsmith, he didn’t feel comfortable with some of those decisions. During his first two months in office, he writes:

"I was briefed on some of the most sensitive counterterrorism operations in the government. Each of these operations was supported by OLC opinions written by my predecessors. As I absorbed the opinions, I concluded that some were deeply flawed: sloppily reasoned, overbroad, and incautious in asserting extraordinary constitutional authorities on behalf of the president. I was astonished, and immensely worried, to discover that some of our most important counterterrorism policies rested on a severely damaged legal foundation. It began to dawn on me that I could not – as I thought I would eventually be asked to do – stand by or reaffirm these opinions."

It would be difficult to rethink prior opinions on such issues in a normal administration. Doing so in this government was particularly hard.

Alberto Gonzales comes off as a nice nonentity. When Goldsmith was vetted for the job, he also met with David Addington. Addington, writes Goldsmith, “was the biggest presence in the room – a large man with large glasses and an imposing salt-and-pepper beard who had been listening to my answers intently. Addington was known throughout the bureaucracy as the best-informed, savviest, and most conservative lawyer in the administration, someone who spoke for and acted with the full backing of the powerful vice president, and someone who crushed bureaucratic opponents.” If anything, Addington was an even more strident advocate of presidential power than was Yoo, who, relates Goldsmith, “frequently told me stories about Addington slaying the legal wimps in the administration who stood as an obstacle to the president’s aggressive anti-terrorism policies.”

Goldsmith’s concerns over administration policy did not turn him into a reflexive Bush critic. For instance, he endorses the notion of a “war on terror” and believes that the president has a right to detain irregular combatants, like Yaser Hamdi, an American citizen captured in Afghanistan. Yet after visiting the Navy brig where Hamdi was held, Goldsmith had some very un-Bushian sentiments:

“Something seemed wrong. It seemed unnecessarily extreme to hold a 22-year-old foot soldier in a remote wing of a run-down prison in a tiny cell, isolated from almost all human contact and with no access to a lawyer. ‘This is what habeas corpus is for,’ I thought to myself, somewhat embarrassed at this squishy sentiment.”

Although he backed the administration’s legal position – he devotes a chapter to the question of enemy combatants and military commissions – he believed the administration’s policy “was excessively legalistic, because it often substituted legal analysis for political judgment, and because it was too committed to expanding the president’s constitutional power.” Administration officials believed that “cooperation and compromise signaled weakness and emboldened the enemies of America and the executive branch.” (Some probably hated the latter more than the former.) Ironically, he concludes, the administration’s policies have made Congress and the courts more suspicious of executive power and more willing to constrain the president.

Perhaps the most interesting story, about which he could not write because so many of the issues remain classified, is warrantless electronic surveillance under FISA. This question led to the much-publicized race between White House Counsel Gonzales and the then-deputy attorney general to Ashcroft’s hospital room. Goldsmith supported a looser legal regime, but complained of “the legal mess that then-White House Counsel Gonzales, David Addington, John Yoo, and others had created in designing the foundations of the Terrorist Surveillance Program.”

Rather than cooperate with either Congress or the FISA court, Goldsmith points out, “top officials in the administration dealt with FISA the way they dealt with other laws they didn’t like: They blew through them in secret based on flimsy legal opinions that they guarded closely so no one could question the legal basis for the operations.” Characteristic of the administration’s attitude was Addington’s comment to Goldsmith: “We’re one bomb away from getting rid of that obnoxious [FISA] court.”

However, torture is the issue that ended Goldsmith’s OLC tenure. He concluded that two Yoo opinions concerning interrogation were erroneous. The documents, he writes, were “legally flawed, tendentious in substance and tone, and overbroad and thus largely unnecessary.” To some they appeared to be works more of political than legal scholarship.

But withdrawing the legal authorization for what can fairly be called torture put interrogators, who had been relying on their government’s promise that their tactics were legal, in an extraordinarily difficult position. Attorney General Ashcroft accepted Goldsmith’s opinion with grace; the White House was more grudging.

Goldsmith asks how the OLC could have issued opinions that “made it seem as though the administration was giving official sanction to torture, and brought such dishonor on the United States, the Bush administration, the Department of Justice, and the CIA?” He answers: fear. Out of fear of future terrorist attacks, the “OLC took shortcuts in its opinion-writing procedures,” shortcuts undoubtedly encouraged by the sustained push for increased presidential powers.

Goldsmith chose this time to resign. He had the usual personal reasons, but, he notes, “important people inside the administration had come to question my fortitude for the job, and my reliability.” That is, his reliability to protect the administration from the Constitution.

The Terror Presidency is one of the most illuminating books on the Bush administration yet to emerge. Although Goldsmith is a hawk in the war on terror, he also believes in the rule of law. And he recognizes the importance of building a popular consensus transcending party. His criticism of the administration is measured but devastating:

"The Terror Presidency’s most fundamental challenge is to establish adequate trust with the American people to enable the president to take the steps needed to fight an enemy that the public does not see and in some respects cannot comprehend. This is an enormously difficult task. The Terror President must educate the public about the threat without unduly scaring it. He must persuade the public of the need for appropriate steps to check the threat, explain his inevitable mistakes, and act with good judgment if an attack comes. And he must convince the public that he is acting in good faith to protect us and is not acting at our expense to enhance or protect himself."

Sadly, the contrast between Goldsmith’s “Terror President” and George W. Bush could not be greater.